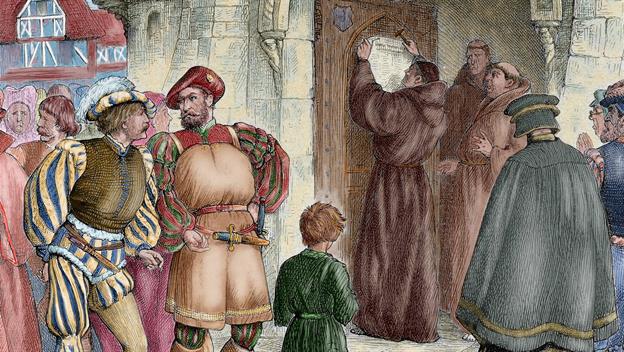

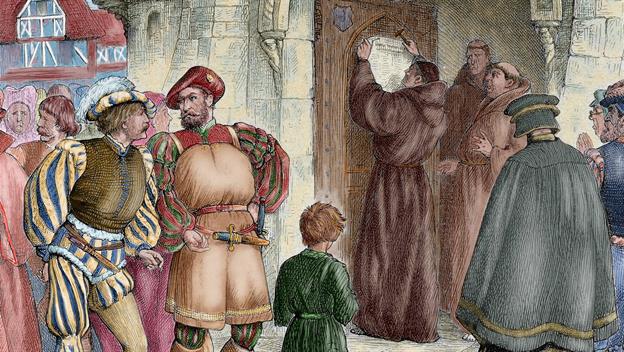

1517

Martin Luther posts 95 theses

On this day in 1517, the priest and scholar Martin Luther

approaches the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany, and

nails a piece of paper to it containing the 95 revolutionary opinions

that would begin the Protestant Reformation.

In his theses, Luther condemned the excesses and corruption of the

Roman Catholic Church, especially the papal practice of asking

payment—called “indulgences”—for the forgiveness of sins. At the time, a

Dominican priest named Johann Tetzel, commissioned by the Archbishop of

Mainz and Pope Leo X, was in the midst of a major fundraising campaign

in Germany to finance the renovation of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Though Prince Frederick III the Wise had banned the sale of indulgences

in Wittenberg, many church members traveled to purchase them. When they

returned, they showed the pardons they had bought to Luther, claiming

they no longer had to repent for their sins.

Luther’s frustration with this practice led him to write the 95

Theses, which were quickly snapped up, translated from Latin into German

and distributed widely. A copy made its way to Rome, and efforts began

to convince Luther to change his tune. He refused to keep silent,

however, and in 1521 Pope Leo X formally excommunicated Luther from the

Catholic Church. That same year, Luther again refused to recant his

writings before the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V of Germany, who issued

the famous Edict of Worms declaring Luther an outlaw and a heretic and

giving permission for anyone to kill him without consequence. Protected

by Prince Frederick, Luther began working on a German translation of the

Bible, a task that took 10 years to complete.

The term “Protestant” first appeared in 1529, when Charles V revoked a

provision that allowed the ruler of each German state to choose whether

they would enforce the Edict of Worms. A number of princes and other

supporters of Luther issued a protest, declaring that their allegiance

to God trumped their allegiance to the emperor. They became known to

their opponents as Protestants; gradually this name came to apply to all

who believed the Church should be reformed, even those outside Germany.

By the time Luther died, of natural causes, in 1546, his revolutionary

beliefs had formed the basis for the Protestant Reformation, which would

over the next three centuries revolutionize Western civilization.

1998

John Glenn returns to space

Nearly four decades after he became the first American to orbit

the Earth, Senator John Hershel Glenn, Jr., is launched into space

again as a payload specialist aboard the space shuttle Discovery.

At 77 years of age, Glenn was the oldest human ever to travel in space.

During the nine-day mission, he served as part of a NASA study on

health problems associated with aging.

Glenn, a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Marine Corps, was among the

seven men chosen by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration

(NASA) in 1959 to become America’s first astronauts. A decorated pilot,

he had flown nearly 150 combat missions during World War II and the

Korean War. In 1957, he made the first nonstop supersonic flight across

the United States, flying from Los Angeles to New York in three hours

and 23 minutes.

In April 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was the first man in space, and his spacecraft, Vostok 1,

made a full orbit before returning to Earth. Less than one month later,

American Alan B. Shepard, Jr., became the first American in space when

his Freedom 7 spacecraft was launched on a suborbital flight.

American “Gus” Grissom made another suborbital flight in July, and in

August Soviet cosmonaut Gherman Titov spent more than 25 hours in space

aboard Vostok 2, making 17 orbits. As a technological power, the

United States was looking very much second-rate compared with its Cold

War adversary. If the Americans wanted to dispel this notion, they

needed a multi-orbital flight before another Soviet space advance

arrived.

On February 20, 1962, NASA and Colonel John Glenn accomplished this feat with the flight of Friendship 7,

a spacecraft that made three orbits of the Earth in five hours. Glenn

was hailed as a national hero, and on February 23 President John F.

Kennedy visited him at Cape Canaveral. Glenn later addressed Congress

and was given a ticker-tape parade in New York City.

Out of a reluctance to risk the life of an astronaut as popular as

Glenn, NASA essentially grounded the “Clean Marine” in the years after

his historic flight. Frustrated with this uncharacteristic lack of

activity, Glenn turned to politics and in 1964 announced his candidacy

for the U.S. Senate from his home state of Ohio and formally left NASA.

Later that year, however, he withdrew his Senate bid after seriously

injuring his inner ear in a fall from a horse. In 1970, following a

stint as a Royal Crown Cola executive, he ran for the Senate again but

lost the Democratic nomination to Howard Metzenbaum. Four years later,

he defeated Metzenbaum, won the general election, and went on to win

reelection three times. In 1984, he unsuccessfully sought the Democratic

nomination for president.

In 1998, Glenn attracted considerable media attention when he returned to space aboard the space shuttle Discovery. In 1999, he retired from his U.S. Senate seat after four consecutive terms in office, a record for the state of Ohio.

1965

Gateway Arch completed

On this day in 1965, construction is completed on the Gateway

Arch, a spectacular 630-foot-high parabola of stainless steel marking

the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial on the waterfront of St.

Louis, Missouri.

The Gateway Arch, designed by Finnish-born, American-educated

architect Eero Saarinen, was erected to commemorate President Thomas

Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and to celebrate St. Louis’

central role in the rapid westward expansion that followed. As the

market and supply point for fur traders and explorers—including the

famous Meriwether Lewis and William Clark—the town of St. Louis grew

exponentially after the War of 1812, when great numbers of people began

to travel by wagon train to seek their fortunes west of the Mississippi

River. In 1947-48, Saarinen won a nationwide competition to design a

monument honoring the spirit of the western pioneers. In a sad twist of

fate, the architect died of a brain tumor in 1961 and did not live to

see the construction of his now-famous arch, which began in February

1963. Completed in October 1965, the Gateway Arch cost less than $15

million to build. With foundations sunk 60 feet into the ground, its

frame of stressed stainless steel is built to withstand both earthquakes

and high winds. An internal tram system takes visitors to the top,

where on a clear day they can see up to 30 miles across the winding

Mississippi and to the Great Plains to the west. In addition to the

Gateway Arch, the Jefferson Expansion Memorial includes the Museum of

Westward Expansion and the Old Courthouse of St. Louis, where two of the

famous Dred Scott slavery cases were heard in the 1860s.

Today, some 4 million people visit the park each year to wander its

nearly 100 acres, soak up some history and take in the breathtaking

views from Saarinen’s gleaming arch.

1904

New York City subway opens

At 2:35 on the afternoon of October 27, 1904, New York City

Mayor George McClellan takes the controls on the inaugural run of the

city’s innovative new rapid transit system: the subway.

While London boasts the world’s oldest underground train network

(opened in 1863) and Boston built the first subway in the United States

in 1897, the New York City subway soon became the largest American

system. The first line, operated by the Interborough Rapid Transit

Company (IRT), traveled 9.1 miles through 28 stations. Running from City

Hall in lower Manhattan to Grand Central Terminal in midtown, and then

heading west along 42nd Street to Times Square, the line finished by

zipping north, all the way to 145th Street and Broadway in Harlem. On

opening day, Mayor McClellan so enjoyed his stint as engineer that he

stayed at the controls all the way from City Hall to 103rd Street.

At 7 p.m. that evening, the subway opened to the general public, and

more than 100,000 people paid a nickel each to take their first ride

under Manhattan. IRT service expanded to the Bronx in 1905, to Brooklyn

in 1908 and to Queens in 1915. Since 1968, the subway has been

controlled by the Metropolitan Transport Authority (MTA). The system now

has 26 lines and 468 stations in operation; the longest line, the 8th

Avenue “A” Express train, stretches more than 32 miles, from the

northern tip of Manhattan to the far southeast corner of Queens.

Every day, some 4.5 million passengers take the subway in New York.

With the exception of the PATH train connecting New York with New Jersey

and some parts of Chicago’s elevated train system, New York’s subway is

the only rapid transit system in the world that runs 24 hours a day,

seven days a week. No matter how crowded or dirty, the subway is one New

York City institution few New Yorkers—or tourists—could do without.

1959

Guggenheim Museum opens in New York City

On this day in 1959, on New York City’s Fifth Avenue, thousands

of people line up outside a bizarrely shaped white concrete building

that resembled a giant upside-down cupcake. It was opening day at the

new Guggenheim Museum, home to one of the world’s top collections of

contemporary art.

Mining tycoon Solomon R. Guggenheim began collecting art seriously

when he retired in the 1930s. With the help of Hilla Rebay, a German

baroness and artist, Guggenheim displayed his purchases for the first

time in 1939 in a former car showroom in New York. Within a few years,

the collection—including works by Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Marc

Chagall—had outgrown the small space. In 1943, Rebay contacted architect

Frank Lloyd Wright and asked him to take on the work of designing not

just a museum, but a “temple of spirit,” where people would learn to see

art in a new way.

Over the next 16 years, until his death six months before the museum

opened, Wright worked to bring his unique vision to life. To Wright’s

fans, the museum that opened on October 21, 1959, was a work of art in

itself. Inside, a long ramp spiraled upwards for a total of a

quarter-mile around a large central rotunda, topped by a domed glass

ceiling. Reflecting Wright’s love of nature, the 50,000-meter space

resembled a giant seashell, with each room opening fluidly into the

next.

Wright’s groundbreaking design drew criticism as well as admiration.

Some felt the oddly-shaped building didn’t complement the artwork. They

complained the museum was less about art and more about Frank Lloyd

Wright. On the flip side, many others thought the architect had achieved

his goal: a museum where building and art work together to create “an

uninterrupted, beautiful symphony.”

Located on New York’s impressive Museum Mile, at the edge of Central

Park, the Guggenheim has become one of the city’s most popular

attractions. In 1993, the original building was renovated and expanded

to create even more exhibition space. Today, Wright’s creation continues

to inspire awe, as well as odd comparisons—a Jello mold! a washing

machine! a pile of twisted ribbon!—for many of the 900,000-plus visitors

who visit the Guggenheim each year.

1781

Victory at Yorktown

Hopelessly trapped at Yorktown, Virginia, British General Lord

Cornwallis surrenders 8,000 British soldiers and seamen to a larger

Franco-American force, effectively bringing an end to the American

Revolution.

Lord Cornwallis was one of the most capable British generals of the

American Revolution. In 1776, he drove General George Washington’s

Patriots forces out of New Jersey, and in 1780 he won a stunning victory

over General Horatio Gates’ Patriot army at Camden, South Carolina.

Cornwallis’ subsequent invasion of North Carolina was less successful,

however, and in April 1781 he led his weary and battered troops toward

the Virginia coast, where he could maintain seaborne lines of

communication with the large British army of General Henry Clinton in

New York City. After conducting a series of raids against towns and

plantations in Virginia, Cornwallis settled in the tidewater town of

Yorktown in August. The British immediately began fortifying the town

and the adjacent promontory of Gloucester Point across the York River.

General George Washington instructed the Marquis de Lafayette, who

was in Virginia with an American army of around 5,000 men, to block

Cornwallis’ escape from Yorktown by land. In the meantime, Washington’s

2,500 troops in New York were joined by a French army of 4,000 men under

the Count de Rochambeau. Washington and Rochambeau made plans to attack

Cornwallis with the assistance of a large French fleet under the Count

de Grasse, and on August 21 they crossed the Hudson River to march south

to Yorktown. Covering 200 miles in 15 days, the allied force reached

the head of Chesapeake Bay in early September.

Meanwhile, a British fleet under Admiral Thomas Graves failed to

break French naval superiority at the Battle of Virginia Capes on

September 5, denying Cornwallis his expected reinforcements. Beginning

September 14, de Grasse transported Washington and Rochambeau’s men down

the Chesapeake to Virginia, where they joined Lafayette and completed

the encirclement of Yorktown on September 28. De Grasse landed another

3,000 French troops carried by his fleet. During the first two weeks of

October, the 14,000 Franco-American troops gradually overcame the

fortified British positions with the aid of de Grasse’s warships. A

large British fleet carrying 7,000 men set out to rescue Cornwallis, but

it was too late.

On October 19, General Cornwallis surrendered 7,087 officers and men,

900 seamen, 144 cannons, 15 galleys, a frigate, and 30 transport ships.

Pleading illness, he did not attend the surrender ceremony, but his

second-in-command, General Charles O’Hara, carried Cornwallis’ sword to

the American and French commanders. As the British and Hessian troops

marched out to surrender, the British bands played the song “The World

Turned Upside Down.”

Although the war persisted on the high seas and in other theaters,

the Patriot victory at Yorktown effectively ended fighting in the

American colonies. Peace negotiations began in 1782, and on September 3,

1783, the Treaty of Paris was signed, formally recognizing the United

States as a free and independent nation after eight years of war.

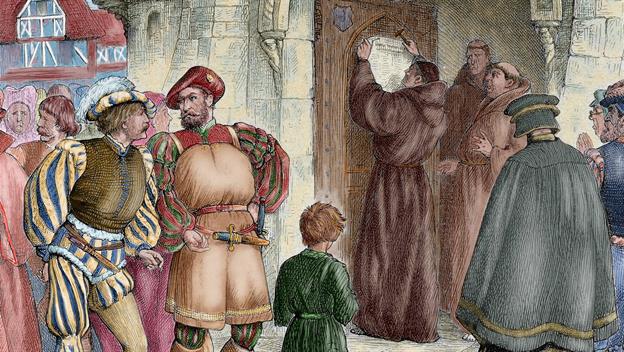

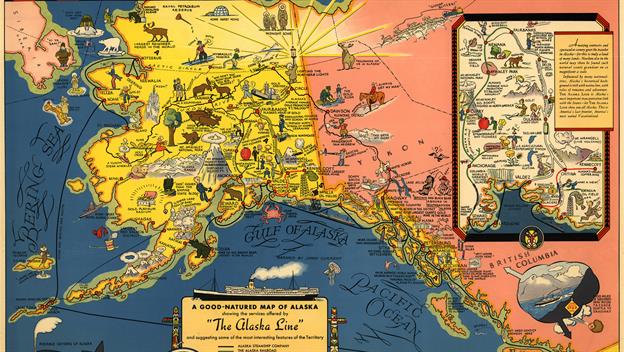

1867

U.S. takes possession of Alaska

On this day in 1867, the U.S. formally takes possession of

Alaska after purchasing the territory from Russia for $7.2 million, or

less than two cents an acre. The Alaska purchase comprised 586,412

square miles, about twice the size of Texas, and was championed by

William Henry Seward, the enthusiasticly expansionist secretary of state

under President Andrew Johnson.

Russia wanted to sell its Alaska territory, which was remote,

sparsely populated and difficult to defend, to the U.S. rather than risk

losing it in battle with a rival such as Great Britain. Negotiations

between Seward (1801-1872) and the Russian minister to the U.S., Eduard

de Stoeckl, began in March 1867. However, the American public believed

the land to be barren and worthless and dubbed the purchase “Seward’s

Folly” and “Andrew Johnson’s Polar Bear Garden,” among other derogatory

names. Some animosity toward the project may have been a byproduct of

President Johnson’s own unpopularity. As the 17th U.S. president,

Johnson battled with Radical Republicans in Congress over Reconstruction

policies following the Civil War. He was impeached in 1868 and later

acquitted by a single vote. Nevertheless, Congress eventually ratified

the Alaska deal. Public opinion of the purchase turned more favorable

when gold was discovered in a tributary of Alaska’s Klondike River in

1896, sparking a gold rush. Alaska became the 49th state on January 3,

1959, and is now recognized for its vast natural resources. Today, 25

percent of America’s oil and over 50 percent of its seafood come from

Alaska. It is also the largest state in area, about one-fifth the size

of the lower 48 states combined, though it remains sparsely populated.

The name Alaska is derived from the Aleut word alyeska, which means

“great land.” Alaska has two official state holidays to commemorate its

origins: Seward’s Day, observed the last Monday in March, celebrates the

March 30, 1867, signing of the land treaty between the U.S. and Russia,

and Alaska Day, observed every October 18, marks the anniversary of the

formal land transfer.

1792

White House cornerstone laid

The cornerstone is laid for a presidential residence in the

newly designated capital city of Washington. In 1800, President John

Adams became the first president to reside in the executive mansion,

which soon became known as the “White House” because its white-gray

Virginia freestone contrasted strikingly with the red brick of nearby

buildings.

The city of Washington was created to replace Philadelphia as the

nation’s capital because of its geographical position in the center of

the existing new republic. The states of Maryland and Virginia ceded

land around the Potomac River to form the District of Columbia, and work

began on Washington in 1791. French architect Charles L’Enfant designed

the area’s radical layout, full of dozens of circles, crisscross

avenues, and plentiful parks. In 1792, work began on the neoclassical

White House building at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue under the guidance of

Irish American architect James Hoban, whose design was influenced by

Leinster House in Dublin and by a building sketch in James Gibbs’ Book of Architecture. President George Washington chose the site.

On November 1, President John Adams was welcomed into the executive

mansion. His wife, Abigail, wrote about their new home: “I pray heaven

to bestow the best of blessings on this house, and on all that shall

hereafter inhabit it. May none but wise men ever rule under this roof!”

In 1814, during the War of 1812, the White House was set on fire

along with the U.S. Capitol by British soldiers in retaliation for the

burning of government buildings in Canada by U.S. troops. The burned-out

building was subsequently rebuilt and enlarged under the direction of

James Hoban, who added east and west terraces to the main building,

along with a semicircular south portico and a colonnaded north portico.

The smoke-stained stone walls were painted white. Work was completed on

the White House in the 1820s.

Major restoration occurred during the administration of President

Harry Truman, and Truman lived across the street for several years in

Blair House. Since 1995, Pennsylvania Avenue between the White House and

Lafayette Square has been closed to vehicular traffic for security

reasons. Today, more than a million tourists visit the White House

annually. It is the oldest federal building in the nation’s capital.

1492

Columbus reaches the New World

After sailing across the Atlantic Ocean, Italian explorer

Christopher Columbus sights a Bahamian island, believing he has reached

East Asia. His expedition went ashore the same day and claimed the land

for Isabella and Ferdinand of Spain, who sponsored his attempt to find a

western ocean route to China, India, and the fabled gold and spice

islands of Asia.

Columbus was born in Genoa, Italy, in 1451. Little is known of his

early life, but he worked as a seaman and then a maritime entrepreneur.

He became obsessed with the possibility of pioneering a western sea

route to Cathay (China), India, and the gold and spice islands of Asia.

At the time, Europeans knew no direct sea route to southern Asia, and

the route via Egypt and the Red Sea was closed to Europeans by the

Ottoman Empire, as were many land routes. Contrary to popular legend,

educated Europeans of Columbus’ day did believe that the world was

round, as argued by St. Isidore in the seventh century. However,

Columbus, and most others, underestimated the world’s size, calculating

that East Asia must lie approximately where North America sits on the

globe (they did not yet know that the Pacific Ocean existed).

With only the Atlantic Ocean, he thought, lying between Europe and

the riches of the East Indies, Columbus met with King John II of

Portugal and tried to persuade him to back his “Enterprise of the

Indies,” as he called his plan. He was rebuffed and went to Spain, where

he was also rejected at least twice by King Ferdinand and Queen

Isabella. However, after the Spanish conquest of the Moorish kingdom of

Granada in January 1492, the Spanish monarchs, flush with victory,

agreed to support his voyage.

On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail from Palos, Spain, with three small ships, the Santa Maria, the Pinta, and the Nina.

On October 12, the expedition reached land, probably Watling Island in

the Bahamas. Later that month, Columbus sighted Cuba, which he thought

was mainland China, and in December the expedition landed on Hispaniola,

which Columbus thought might be Japan. He established a small colony

there with 39 of his men. The explorer returned to Spain with gold,

spices, and “Indian” captives in March 1493 and was received with the

highest honors by the Spanish court. He was the first European to

explore the Americas since the Vikings set up colonies in Greenland and

Newfoundland in the 10th century.

During his lifetime, Columbus led a total of four expeditions to the

New World, discovering various Caribbean islands, the Gulf of Mexico,

and the South and Central American mainlands, but he never accomplished

his original goal—a western ocean route to the great cities of Asia.

Columbus died in Spain in 1506 without realizing the great scope of what

he did achieve: He had discovered for Europe the New World, whose

riches over the next century would help make Spain the wealthiest and

most powerful nation on earth.

2003

Arnold Schwarzenegger becomes California governor

On this day in 2003, actor Arnold Schwarzenegger is elected

governor of California, the most populous state in the nation with the

world’s fifth-largest economy. Despite his inexperience, Schwarzenegger

came out on top in the 11-week campaign to replace Gray Davis, who had

earlier become the first United States governor to be recalled by the

people since 1921. Schwarzenegger was one of 135 candidates on the

ballot, which included career politicians, other actors, and one

adult-film star.

Born in Thal, Austria, on July 30, 1947, Arnold Schwarzenegger began

body-building as a teenager. He won the first of four “Mr. Universe”

body-building championships at the age of 20, and moved to the United

States in 1968. He also went on to win a then-record seven “Mr.

Olympia” championships, securing his reputation as a body-building

legend, and soon began appearing in films. Schwarzenegger first

attracted mainstream public attention for a Golden Globe®-winning

performance in Stay Hungry (1976) and his appearance in the 1977 documentary Pumping Iron. At the same time, he was working on a B.A. at the University of Wisconsin, from which he graduated in 1979.

Schwarzenegger’s film career took off after his starring turn in 1982’s Conan the Barbarian. In 1983, he became a U.S. citizen; the next year he made his most famous film, The Terminator,

directed by James Cameron. Although his acting talent is probably

aptly described as limited, Schwarzenegger went on to become one of the

most sought-after action-film stars of the 1980s and early 1990s and

enjoyed an extremely lucrative career. The actor’s romantic life also

captured the attention of the American public: he married television

journalist and lifelong Democrat Maria Shriver, niece of the late

President John F. Kennedy, in 1986.

With his film career beginning to stagnate, Schwarzenegger, a staunch

supporter of the Republican party who had long been thought to harbor

political aspirations, announced his candidacy for governor of

California during an appearance on The Tonight Show with Jay Leno.

Aside from his well-known stint serving as chairman of the President s

Council on Physical Fitness and Sports under President George H.W.

Bush, Schwarzenegger had little political experience. His campaign,

which featured his use of myriad one-liners well-known from his movie

career, was dogged by criticism of his use of anabolic steroids, as well

as allegations of sexual misconduct and racism. Still, Schwarzenegger

was able to parlay his celebrity into a win, appealing to weary

California voters with talk of reform. He beat his closest challenger,

the Democratic lieutenant governor Cruz Bustamante, by more than 1

million votes.

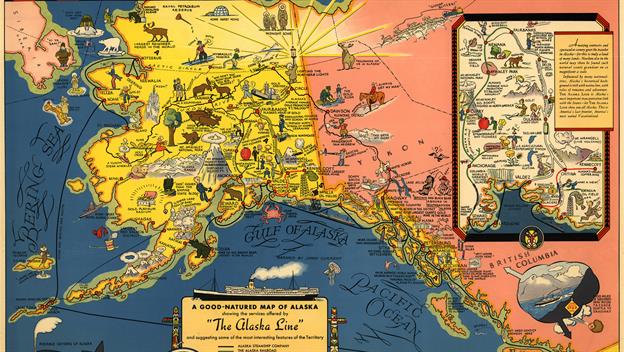

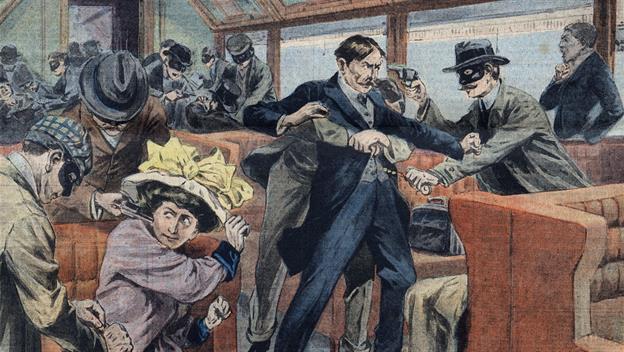

1866

First U.S. train robbery

On this day in 1866, the Reno gang carries out the first

robbery of a moving train in the U.S., making off with over $10,000 from

an Ohio & Mississippi train in Jackson County, Indiana. Prior to

this innovation in crime, holdups had taken place only on trains sitting

at stations or freight yards.

This new method of sticking up moving trains in remote locations low

on law enforcement soon became popular in the American West, where the

recently constructed transcontinental and regional railroads made

attractive targets. With the western economy booming, trains often

carried large stashes of cash and precious minerals. The sparsely

populated landscape provided bandits with numerous isolated areas

perfect for stopping trains, as well as plenty of places to hide from

the law. Some gangs, like Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch, found robbing

trains so easy and lucrative that, for a time, they made it their

criminal specialty. Railroad owners eventually got wise and fought back,

protecting their trains’ valuables with large safes, armed guards and

even specially fortified boxcars. Consequently, by the late 1800s,

robbing trains had turned into an increasingly tough and dangerous job.

As for the Reno gang, which consisted of the four Reno brothers and

their associates, their reign came to an end in 1868 when they all were

finally captured after committing a series of train robberies and other

criminal offenses. In December of that year, a mob stormed the Indiana

jail where the bandits were being held and meted out vigilante justice,

hanging brothers Frank, Simeon and William Reno (their brother John had

been caught earlier and was already serving time in a different prison)

and fellow gang member Charlie Anderson.

1947

First presidential speech on TV

On this day in 1947, President Harry Truman (1884-1972) makes the

first-ever televised presidential address from the White House, asking

Americans to cut back on their use of grain in order to help starving

Europeans. At the time of Truman’s food-conservation speech, Europe was

still recovering from World War II and suffering from famine. Truman,

the 33rd commander in chief, worried that if the U.S. didn’t provide

food aid, his administration’s Marshall Plan for European economic

recovery would fall apart. He asked farmers and distillers to reduce

grain use and requested that the public voluntarily forgo meat on

Tuesdays, eggs and poultry on Thursdays and save a slice of bread each

day. The food program was short-lived, as ultimately the Marshall Plan

succeeded in helping to spur economic revitalization and growth in

Europe. In 1947,television was still in its infancy and the number of TV

sets in U.S. homes only numbered in the thousands (by the early 1950s,

millions of Americans owned TVs); most people listened to the radio for

news and entertainment. However, although the majority of Americans

missed Truman’s TV debut, his speech signaled the start of a powerful

and complex relationship between the White House and a medium that would

have an enormous impact on the American presidency, from how candidates

campaigned for the office to how presidents communicated with their

constituents. Each of Truman’s subsequent White House speeches,

including his 1949 inauguration address, was televised. In 1948, Truman

was the first presidential candidate to broadcast a paid political ad.

Truman pioneered the White House telecast, but it was President Franklin

Roosevelt who was the first president to appear on TV–from the World’s

Fair in New York City on April 30, 1939. FDR’s speech had an extremely

limited TV audience, though, airing only on receivers at the fairgrounds

and at Radio City in Manhattan.