1938

Nazis launch Kristallnacht

On this day in 1938, in an event that would foreshadow the

Holocaust, German Nazis launch a campaign of terror against Jewish

people and their homes and businesses in Germany and Austria. The

violence, which continued through November 10 and was later dubbed

“Kristallnacht,” or “Night of Broken Glass,” after the countless smashed

windows of Jewish-owned establishments, left approximately 100 Jews

dead, 7,500 Jewish businesses damaged and hundreds of synagogues, homes,

schools and graveyards vandalized. An estimated 30,000 Jewish men were

arrested, many of whom were then sent to concentration camps for several

months; they were released when they promised to leave Germany.

Kristallnacht represented a dramatic escalation of the campaign started

by Adolf Hitler in 1933 when he became chancellor to purge Germany of

its Jewish population.

The Nazis used the murder of a low-level German diplomat in Paris by a

17-year-old Polish Jew as an excuse to carry out the Kristallnacht

attacks. On November 7, 1938, Ernst vom Rath was shot outside the German

embassy by Herschel Grynszpan, who wanted revenge for his parents’

sudden deportation from Germany to Poland, along with tens of thousands

of other Polish Jews. Following vom Rath’s death, Nazi propaganda

minister Joseph Goebbels ordered German storm troopers to carry out

violent riots disguised as “spontaneous demonstrations” against Jewish

citizens. Local police and fire departments were told not to interfere.

In the face of all the devastation, some Jews, including entire

families, committed suicide.

In the aftermath of Kristallnacht, the Nazis blamed the Jews and

fined them 1 billion marks (or $400 million in 1938 dollars) for vom

Rath’s death. As repayment, the government seized Jewish property and

kept insurance money owed to Jewish people. In its quest to create a

master Aryan race, the Nazi government enacted further discriminatory

policies that essentially excluded Jews from all aspects of public life.

Over 100,000 Jews fled Germany for other countries after

Kristallnacht. The international community was outraged by the violent

events of November 9 and 10. Some countries broke off diplomatic

relations in protest, but the Nazis suffered no serious consequences,

leading them to believe they could get away with the mass murder that

was the Holocaust, in which an estimated 6 million European Jews died.

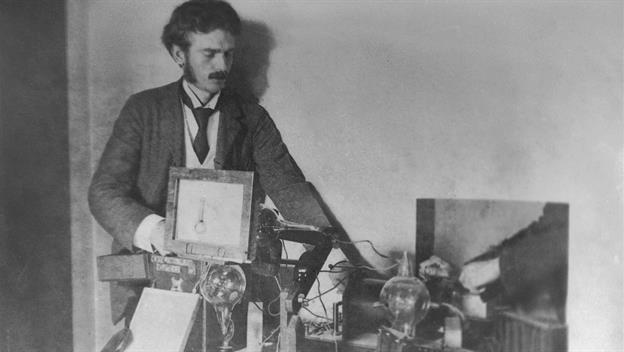

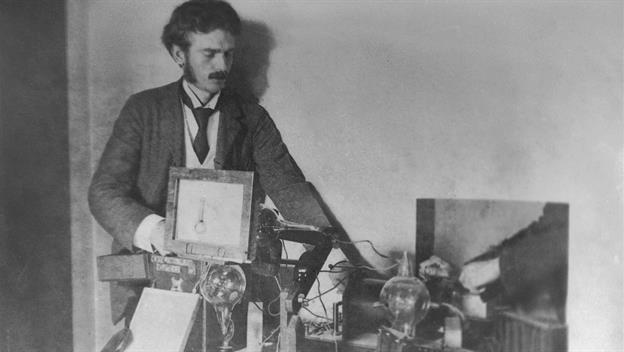

1895

German scientist discovers X-rays

On this day in 1895, physicist Wilhelm Conrad Rontgen

(1845-1923) becomes the first person to observe X-rays, a significant

scientific advancement that would ultimately benefit a variety of

fields, most of all medicine, by making the invisible visible. Rontgen’s

discovery occurred accidentally in his Wurzburg, Germany, lab, where he

was testing whether cathode rays could pass through glass when he

noticed a glow coming from a nearby chemically coated screen. He dubbed

the rays that caused this glow X-rays because of their unknown nature.

X-rays are electromagnetic energy waves that act similarly to light

rays, but at wavelengths approximately 1,000 times shorter than those of

light. Rontgen holed up in his lab and conducted a series of

experiments to better understand his discovery. He learned that X-rays

penetrate human flesh but not higher-density substances such as bone or

lead and that they can be photographed.

Rontgen’s discovery was labeled a medical miracle and X-rays soon

became an important diagnostic tool in medicine, allowing doctors to see

inside the human body for the first time without surgery. In 1897,

X-rays were first used on a military battlefield, during the Balkan War,

to find bullets and broken bones inside patients.

Scientists were quick to realize the benefits of X-rays, but slower

to comprehend the harmful effects of radiation. Initially, it was

believed X-rays passed through flesh as harmlessly as light. However,

within several years, researchers began to report cases of burns and

skin damage after exposure to X-rays, and in 1904, Thomas Edison’s

assistant, Clarence Dally, who had worked extensively with X-rays, died

of skin cancer. Dally’s death caused some scientists to begin taking the

risks of radiation more seriously, but they still weren’t fully

understood. During the 1930s, 40s and 50s, in fact, many American shoe

stores featured shoe-fitting fluoroscopes that used to X-rays to enable

customers to see the bones in their feet; it wasn’t until the 1950s that

this practice was determined to be risky business. Wilhelm Rontgen

received numerous accolades for his work, including the first Nobel

Prize in physics in 1901, yet he remained modest and never tried to

patent his discovery. Today, X-ray technology is widely used in

medicine, material analysis and devices such as airport security

scanners.

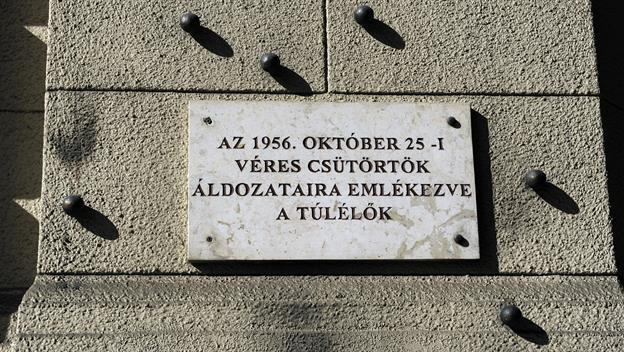

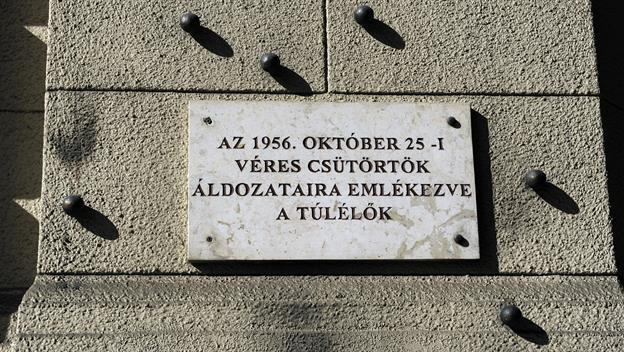

1956

Soviets put brutal end to Hungarian revolution

A spontaneous national uprising that began 12 days before in

Hungary is viciously crushed by Soviet tanks and troops on this day in

1956. Thousands were killed and wounded and nearly a quarter-million

Hungarians fled the country.

The problems in Hungary began in October 1956, when thousands of

protesters took to the streets demanding a more democratic political

system and freedom from Soviet oppression. In response, Communist Party

officials appointed Imre Nagy, a former premier who had been dismissed

from the party for his criticisms of Stalinist policies, as the new

premier. Nagy tried to restore peace and asked the Soviets to withdraw

their troops. The Soviets did so, but Nagy then tried to push the

Hungarian revolt forward by abolishing one-party rule. He also announced

that Hungary was withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact (the Soviet bloc’s

equivalent of NATO).

On November 4, 1956, Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest to crush, once

and for all, the national uprising. Vicious street fighting broke out,

but the Soviets’ great power ensured victory. At 5:20 a.m., Hungarian

Prime Minister Imre Nagy announced the invasion to the nation in a grim,

35-second broadcast, declaring: “Our troops are fighting. The

Government is in place.” Within hours, though, Nagy sought asylum at the

Yugoslav Embassy in Budapest. He was captured shortly thereafter and

executed two years later. Nagy’s former colleague and imminent

replacement, János Kádár, who had been flown secretly from Moscow to the

city of Szolnok, 60 miles southeast of the capital, prepared to take

power with Moscow’s backing.

The Soviet action stunned many people in the West. Soviet leader

Nikita Khrushchev had pledged a retreat from the Stalinist policies and

repression of the past, but the violent actions in Budapest suggested

otherwise. An estimated 2,500 Hungarians died and 200,000 more fled as

refugees. Sporadic armed resistance, strikes and mass arrests continued

for months thereafter, causing substantial economic disruption.

Inaction on the part of the United States angered and frustrated many

Hungarians. Voice of America radio broadcasts and speeches by President

Dwight D. Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had

recently suggested that the United States supported the “liberation” of

“captive peoples” in communist nations. Yet, as Soviet tanks bore down

on the protesters, the United States did nothing beyond issuing public

statements of sympathy for their plight.

1947

Spruce Goose flies

The Hughes Flying Boat—the largest aircraft ever built—is

piloted by designer Howard Hughes on its first and only flight. Built

with laminated birch and spruce, the massive wooden aircraft had a

wingspan longer than a football field and was designed to carry more

than 700 men to battle.

Howard Hughes was a successful Hollywood movie producer when he

founded the Hughes Aircraft Company in 1932. He personally tested

cutting-edge aircraft of his own design and in 1937 broke the

transcontinental flight-time record. In 1938, he flew around the world

in a record three days, 19 hours, and 14 minutes.

Following the U.S. entrance into World War II in 1941, the U.S.

government commissioned the Hughes Aircraft Company to build a large

flying boat capable of carrying men and materials over long distances.

The concept for what would become the “Spruce Goose” was originally

conceived by the industrialist Henry Kaiser, but Kaiser dropped out of

the project early, leaving Hughes and his small team to make the H-4

a reality. Because of wartime restrictions on steel, Hughes decided to

build his aircraft out of wood laminated with plastic and covered with

fabric. Although it was constructed mainly of birch, the use of spruce

(along with its white-gray color) would later earn the aircraft the

nickname Spruce Goose. It had a wingspan of 320 feet and was powered by

eight giant propeller engines.

Development of the Spruce Goose cost a phenomenal $23 million and

took so long that the war had ended by the time of its completion in

1946. The aircraft had many detractors, and Congress demanded that

Hughes prove the plane airworthy. On November 2, 1947, Hughes obliged,

taking the H-4 prototype out into Long Beach Harbor, CA for an

unannounced flight test. Thousands of onlookers had come to watch the

aircraft taxi on the water and were surprised when Hughes lifted his

wooden behemoth 70 feet above the water and flew for a mile before

landing.

Despite its successful maiden flight, the Spruce Goose never went

into production, primarily because critics alleged that its wooden

framework was insufficient to support its weight during long flights.

Nevertheless, Howard Hughes, who became increasingly eccentric and

withdrawn after 1950, refused to neglect what he saw as his greatest

achievement in the aviation field. From 1947 until his death in 1976, he

kept the Spruce Goose prototype ready for flight in an enormous,

climate-controlled hangar at a cost of $1 million per year. Today, the

Spruce Goose is housed at the Evergreen Aviation Museum in McMinnville,

Oregon.